Sometimes, you find yourself in the middle of nowhere.

And sometimes, in the middle of nowhere, you find yourself.

-Stacy Westfall

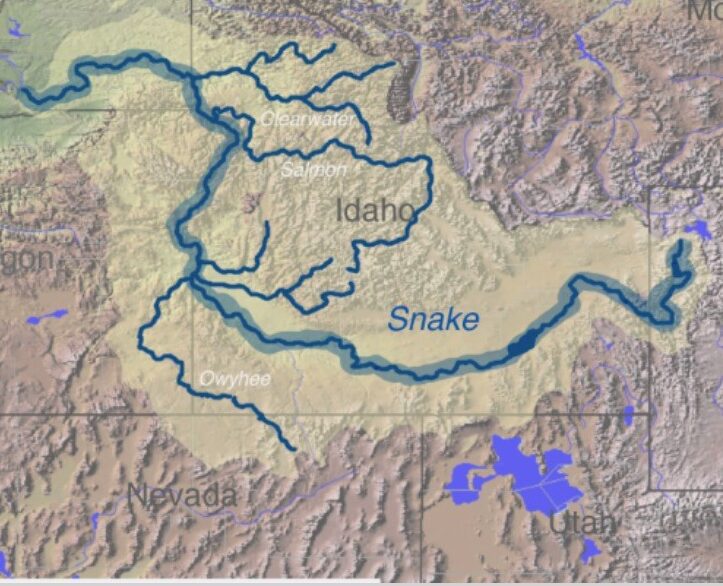

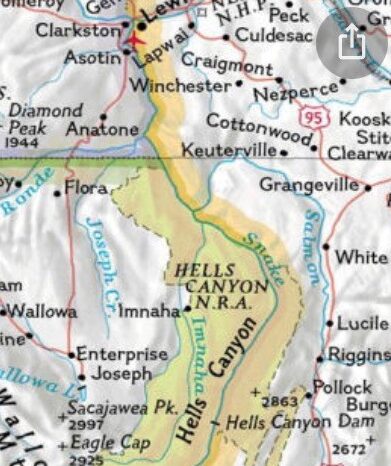

I’m sitting on the large tubular bow of our rubber raft, like a figurehead, as we ride on smooth current down the Snake River. Between my legs, almost under my crotch, is a ring that has a rope attached to it, used for securing the boat to the shore when we beach it. I have a death-grip on that rope with my left hand, as close to the ring as I can get it. I’m almost sitting on my hand. My right hand is free but ready to grab hold if needed. My feet are dangling over the prow just above the water and my butt is dangling over the floor of the raft. I’m ready for the next rapids. The guides call this position, “riding the bull.”

As I get ready for the ride ahead, I look out and see the river around the raft is remarkably still, except for large areas of calm upwelling water, gentle eddies and tiny swirls all linked in an arc. I say remarkably, because I can see smooth, erosion-worn rocks on the bottom seemingly fly past to our rear as we rush downstream with the current. I glance over at Phyllis, who is sitting on the forward bench just behind me. She is bracing herself as well because, up ahead is white-water; churning, roiling waves of tormented rive as it crashes inexorably over unseen boulders on the river bed and bounce off the rocks onshore. The waves form a kind of an inverted “V,” whose apex is where most of the water is channeled – that’s where we’re headed. In places, the water rises, then crashes over a large unseen obstacle, forming a kind of a hole in the river on the downstream side. Water backwashes into the space created this way, causing a wave to flow upstream, cresting in a big white-peaked wall of green wetness that crashes down into the depression. “Green holes,” the guides call them (the river is quite green, due to algae) and they are something to be avoided as a boat can get stuck in there and have trouble getting out. Then, of course, there’s always the risk of getting flipped over…

We seem to go over a ledge, like over a small waterfall, and I’m staring down into a deep trough. I look up and see I’m about to be slammed with a froth-topped building of green wetness that rises up over my head. With my free hand, I pull my hat down tight over my skull and brace for impact. “Yippee!” I shout, waving my right arm above my head, like in the pictures I’ve seen of bronco-busters. The wall slams into me. Sploosh! It’s like high-diving into an emerald swimming pool with a bellyflop. Miraculously, my hat stays on. Dripping from head to foot, I hold on tight as we plunge down into another trough and the process repeats itself. After a few more inundations, the river smooths out a bit, though we’re still in rapids, and I lose my perch, sliding back onto the raft floor. I flounder there for a bit, on my back like an upset turtle, arms and legs flailing about, unable to get purchase or get them under me. I feel something grab my personal flotation device by the shoulder strap and I’m yanked upright onto my feet again.

“Thanks, Bryce,” I tell our guide. “I needed that!” I feel a big grin stretch out on my face. I sit down next to Phyllis and glance at her. She is also soaked and smiling. Looking up, I see we’re on smooth flat water again. But there’s more white-water not too far ahead.

“My turn!” says Phyllis and she gets up to take my place.

On the stretches of smooth water where there are no rapids, we float down the river at around eight or nine knots. Tall steep mountains loom up close on both sides with cliffs that plunge down into the water. The rugged horizon, not that far away, is silhouetted by a dark blue sky – so much bluer that what I’m used to on the East Coast. The contrast of this blue with the drought-fraught pastel tan and yellow of the gorge’s walls is striking. Here and there, in places where there are spots flat enough to hold them, we can see bighorn sheep and even deer. Kingfishers and chukars flit about over the water and hang out on rocks and bushes near the river’s edge. Herons wade in the shallows, mergansers float in the calmer water and we even see a bald eagle or two.

In the early twentieth century, there were a few people who tried to move into the canyon and scratch out a living. Their cabins have since all been bought up by the government and abandoned so the canyon could be made into a wilderness area. Some of them are still standing and we stop and explore a few. There were some attempts at mining here and there, none of them very successful, where people were looking for lead, zinc, molybdenum, silver, gold and other minerals. The holes they left behind are still there, although the entrances have been blocked off for safety. Pictographs, left by ancient aborigines, some perhaps as old as 10,000 years or more, can be found on rock walls easily accessible from the river. Hell’s Canyon has plenty to do and see, on and off the water.

I hope Waldo is having as much fun as I am!

I miss the little guy.